Michael Pearn, Senior Consultant | August 5, 2021

Published in February 2014, Open ID Connect or ‘OIDC’ is an open authentication standard built on top of the existing OAuth open authorization standard.

This blog will outline some practical understanding of working with OIDC, some comparisons to SAML for situations where both could be used, and how to use it in some basic ways with an Azure implementation.

This Nate Barbettini video on breaking down Open ID and OAuth 2.0 ‘in plain English’ is probably the best theoretical understanding of the open standard that I can recommend.

If you’ve digested some of this theory already, then some key points that I’ve found after working with it with implementations might make this easier to understand:

If you’d like to watch a clear breakdown about the difference between the IETF (ietf.org), Oauth.net (OAuth2) and Open ID Foundation (OIDC) behind all of these web standards, then the first section of this is the best explanation I can recommend.

Like with any open standard, an identity vendor (say Azure, Okta, Auth0 etc.) will implement and potentially interpret certain aspects of that standard in their implementations, and therefore no two vendor’s OIDC implementations are exactly the same. I’ll touch on a few examples that I’ve discovered later in the blog.

In 2021, we no longer have just users (or systems impersonating users) with accounts and passwords accessing traditional web applications with front and backends – we have all sorts of access scenarios, for example TVs that don’t have Internet browsers etc. A simple username and password does not cater for a significant number of 2021’s authentication scenarios.

‘Web’ applications themselves have evolved – for example: Single Page Apps (SPAs) don’t have a traditional server backend for example and code is entirely executed locally on the machine.

OAuth (and therefore OIDC) has therefore grown (and also consolidated as I’ll outline) to accommodate these increasingly different types of authentication and authorization scenarios.

More recently, the OAuth.net organization has released its specifications for OAuth 2.1 but these can be largely considered as resolving and consolidating the number of RFC standards that falls under the existing umbrella. For example, the Implicit flow type has been largely redundant due to the security issues with it and largely replaced with Authorization Code + Private Key (PKCE) Exchange.

In essence OAuth 2.1 outlines, in terms of ‘how to use it’, largely three grant types:

These ‘grant types’ are a key part of understanding the three major flows that OAuth2.1 and OIDC can be used in products for authorisation and authentication. Typically, only Auth Code and Client Credentials would be used in a typical organization that only consume OIDC aware web-based applications or OAuth enabled Web APIs.

If an organization say wants to use their identity provider’s OIDC authorization service, with a third-party application that is OIDC aware, then I’ll provide some general advice as good practice and good security hygiene:

In a lot of Enterprise application situations you’ll want to setup Federation of a corporate identity provider such as Azure to a cloud web app - for example, Salesforce.com - the vendor will often provide now a choice between using OIDC and SAML protocols for authentication and authorization.

This comparison will largely ignore that OIDC can often be used in many more authentications scenarios where SAML cannot, however we’ll use an example of a cloud identity provider communicating with a remote web-based SaaS application which offers both SAML and OIDC integrations.

By and large, OIDC presents significant benefits over SAML namely:

The downside however, in some cases, is that using Open ID Connect in an Enterprise can be confusing initially due to the ability to troubleshoot issues. SAML, as it primarily uses the browser’s front channel to pass SAML claims between the identity provider and the remote application, can be easier to troubleshoot as you can install many SAML ‘trace’ tools that can inspect a SAML claim in transition (assuming the SAML traffic isn’t encrypted).

If you’re sending a custom set of SAML claims to an application and you want to verify both the claim name and value, you can easily do so using these tools. Troubleshooting OIDC is more difficult as you will often not see the ID or Access tokens in the browser due to improved security, or its being sent via the back channel if one exists. This can be replaced however using other tools such as Postman Collections and JWT viewers (which I’ll outline later in this blog).

I’ll now outline how it can be quite straight forward to configure an identity provider, which in this case is Azure, to configure that provider with a ‘client’ or ‘application’ (terms that are often used interchangeably) that will be used to issue new ID and Access Tokens for a remote cloud app that supports OIDC.

In this case, I’ll be outlining how to use Authorization Code grant type to support this (I won’t include PKCE which is strongly recommended to keep the process shorter).

This setup will outline how to:

All Azure tenants come with specific OIDC endpoints ready for a user and application to communicate with. The easiest is to start with the ‘well known’ endpoint to find all other OIDC endpoints, that you can then supply to an application vendor which supports OIDC.

This would be equivalent (but not quite) to a SAML’s ‘metadata’ endpoint. As I outlined earlier, in my experience, SAML metadata endpoints aren’t consistently named or often vendors won’t implement them.

However, all Azure tenants publish their OIDC endpoint at the following location (assuming a corporate Tenant): https://login.microsoftonline.com/{tenant}/v2.0/.well-known/openid-configuration.

The ‘/.well-known/open-id/configuration’ path is a common standard path across all identity vendors.

The first step is to setup an ‘application registration’:

This case I call the ‘quick and dirty’ method, if you’re just wanting to see what Azure will expose to a third party OIDC application in terms of both the ID and Access tokens (JWT format).

This method is extraordinarily simple, as this method will simulate an ‘Implicit’ grant type and flow and request the ID and Access tokens direct from the ‘/authorize’ endpoint. This is not recommended for any production systems, and ‘Implicit’ is banned in the OAuth2.1 spec, but it’s the quickest way to diagnose potentially data quality issues with the JWT.

Typically, to compose this URL you combine the following elements:

https://login.microsoftonline.com/<tenantName or ID>/oauth2/v2.0/authorize ?client_id=<AppID of the JWT app you just created>&nonce=defaultNonce&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fjwt.ms&scope=openid+email+profile&response_type=<id_token and/or token>

I personally prefer this method, as it simulates more accurately what an OIDC web application is performing in order to authenticate a user. It also represents use of both the ‘front channel’ (browser) and simulating a backend web app server i.e. ‘back channel’ calling the ‘/token’ endpoint to retrieve the tokens.

https://login.microsoftonline.com/<tenantName or ID>/oauth2/v2.0/authorize ?client_id=<AppID of the JWT app you just created%gt;&nonce=defaultNonce&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fjwt.ms&scope=openid+email+profile&response_type=code

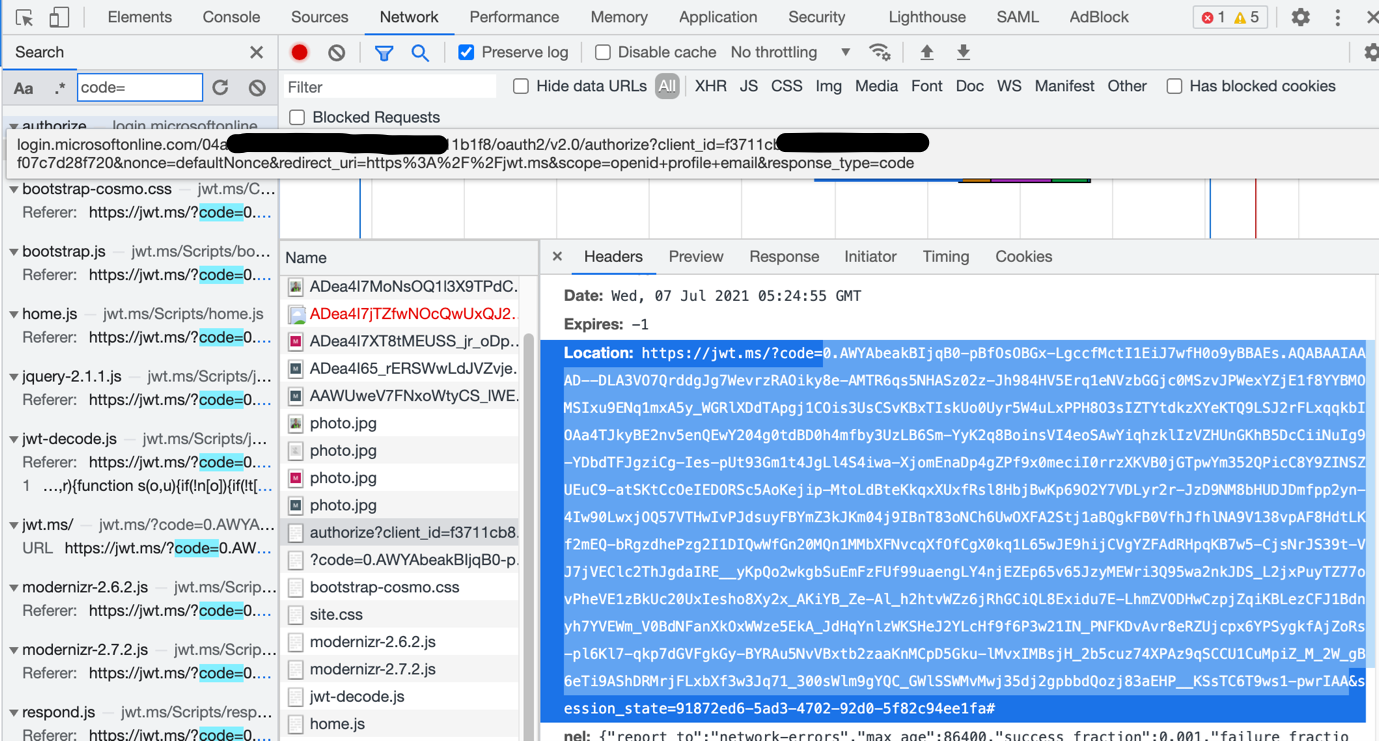

Once you’ve composed your URL, open a browser with F12 diagnostics and go to the ‘Network’ tab. Paste the above URL into your browser and authenticate to Microsoft Azure. Once complete, perform a search for ‘code=’ and you’ll see a bunch of returned values. If you locate on of them, you’ll see something similar to the following:

The Authorization code that is of value is the value after the ‘?code=’ and before the ‘&session_state’ values. For example in the above it starts with ‘0.AWYAbea’

The next part is to simulate what a traditional web server does when it then retrieves the tokens on behalf of the authenticated user.

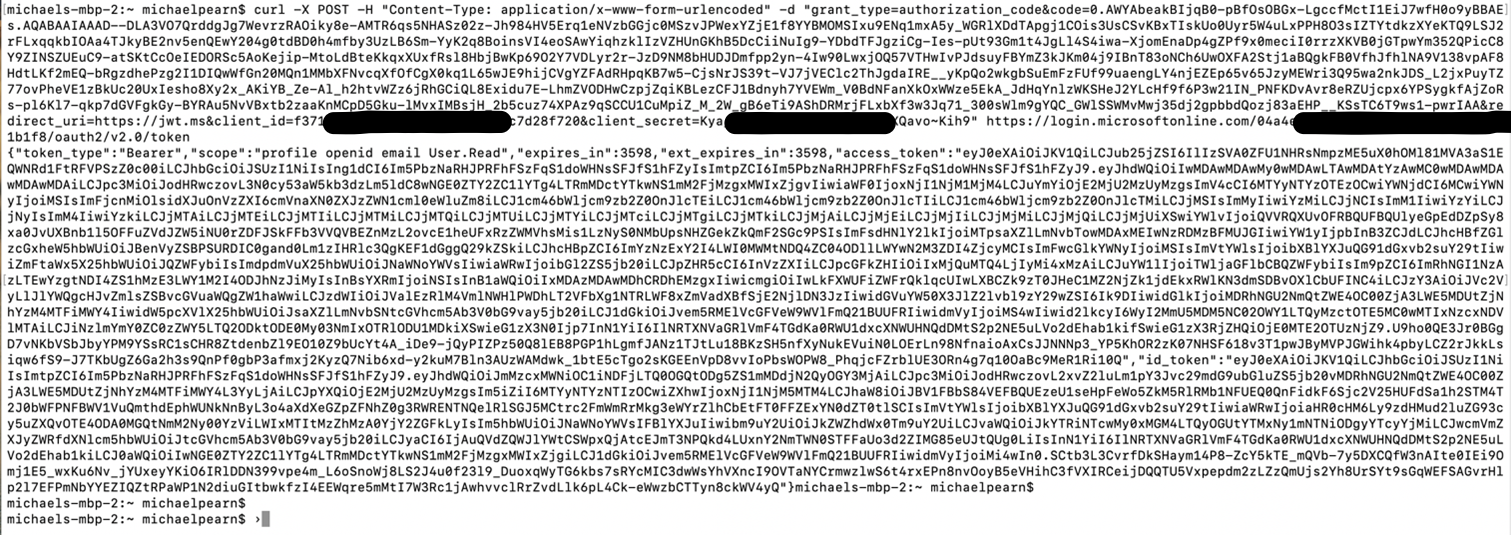

For this, I use a CURL command comprising of the following:

curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "grant_type=authorization_code&code=<Auth code value returned in Part 1>&redirect_uri=https://jwt.ms&client_id=<client ID>&client_secret=<client Secret>” https://login.microsoftonline.com/<Tenant ID>/oauth2/v2.0/token

You’ll get back a big JSON payload starting with:

{“token_type”:”Bearer”…

The key values being returned will be:

“access_token”: and: “id_token”:

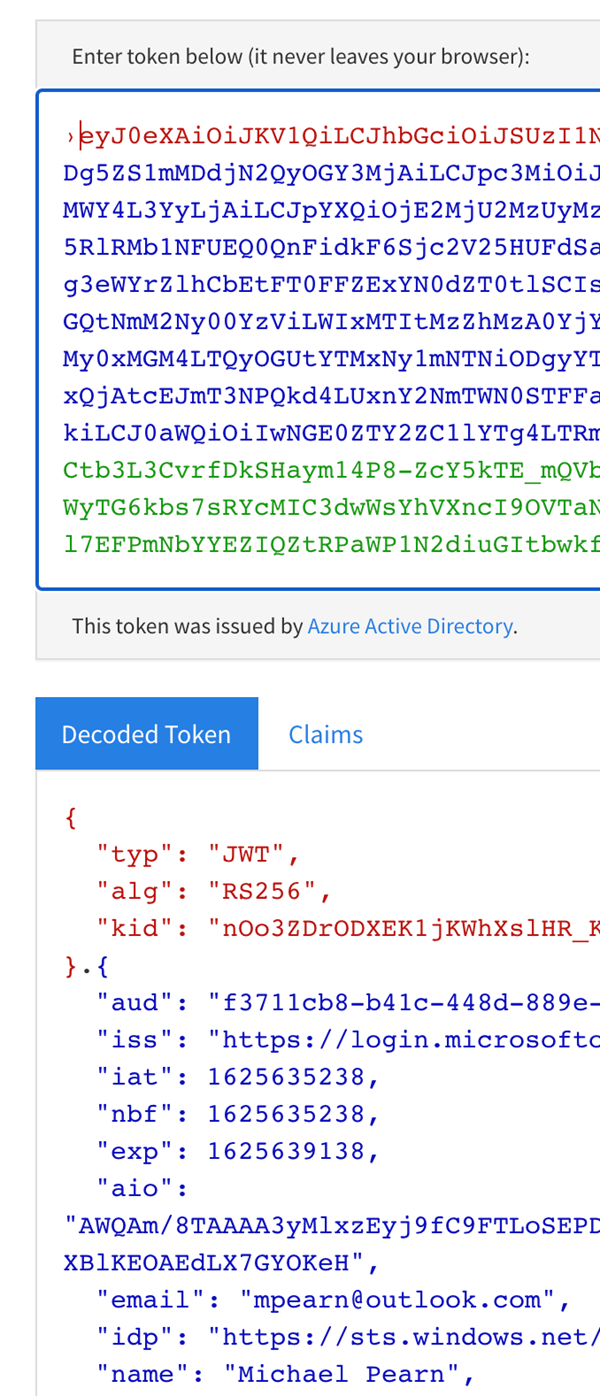

You can then browse to: https://jwt.ms or https://jwt.io (to name two examples) and then copy in the raw JSON encoded values of the tokens:

In this blog, I went over the history of where the Open ID Connect standard has been derived from, its relationship to the OAuth 2.1 spec and also how to understand the basis of its JWT tokens with an Azure example.

In future blogs, I’ll explore how Private Key Code Exchange (or ‘PKCE’) further secures the Authorization code grant type for use with Single Page Apps or ‘SPAs’ and by removing tokens from browser history which could be comprised.

Request a consultation with one of our security specialists today or sign up to receive our monthly newsletter via email.

Get in touch Sign up!